Colors and Memory. Portraits of Merchants in Armenian Illuminated Gospels

Descriptions of merchants in ancient and medieval sources range from admiration for their courage, exotic travels and as protagonists of adventures, to shrewd and dishonest barterers set on cheating their clients. My task in the ArmEn project is to trace the representation of Armenian merchants in manuscript illuminations and place it in a wider Eurasian context.

Although only few examples of merchants’ portraits have thus far come to light, Armenian tradesmen appear as rich patrons who sponsored the production of manuscripts. Usually, they donated these codices to monasteries as a sign of devotion, often appended to a request for intercession before God.

As any other commissioner of manuscripts, merchants too left a memory of their pious deed in the text of colophons. But they also wished to be remembered through the colors of a miniature.

These are rare images, which highlight a fascinating iconographic repertoire, almost completely unexplored from the point of view of the figurative culture of Armenia and medieval Eurasia in general.

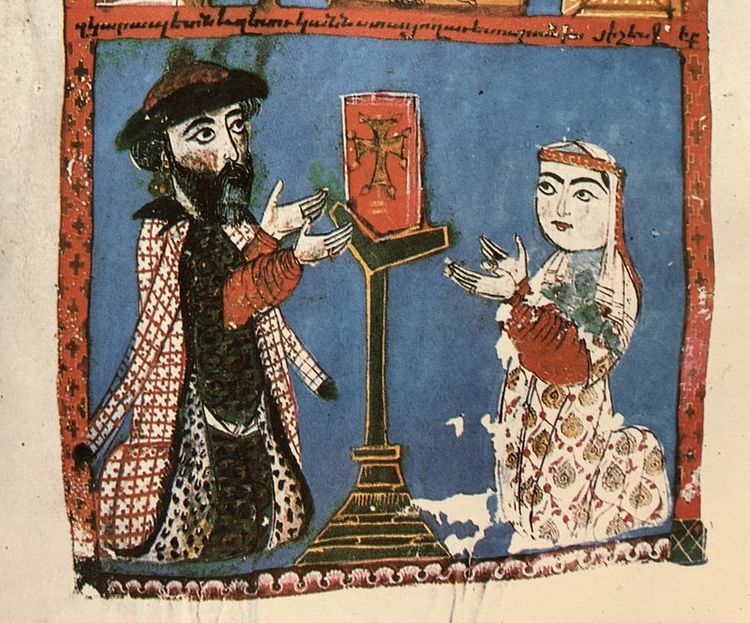

These representations are important from several points of view. Firstly, these portraits provide information on a specific “category” of people belonging to the middle-class Armenian élite. At the same time, they allow us a glimpse into the fashion and customs of the period. In miniatures merchants wear clothes made of precious fabrics, decorated with floral or geometric patterns. Sometimes they don simple tunics but with typically Arab-style headdresses. In addition to the aesthetic aspect, a clear symbol of wealth and splendor, sometimes merchants are keen on being presented together with members of their family – wife or relatives (Fig. 1).

The merchant class, thus, expressed its piety and wished to be remembered not only for the foundation of churches (as the wealthy Tigran Honents‘ of Ani) and other structures, but also for something more intimate and of value – the production of Gospels. In fact, manuscripts are one of the most valuable objects that transmitted the Armenian culture over the centuries, becoming an identity symbol of a people through which to pass on its language. By virtue of this importance, they were a perfect locus within which to guarantee a long memory of oneself. In the Armenian Gospels, merchants appear as cultured patrons, as if challenging the idea that they were ‘mere’ buyers dedicated to the exchange of precious goods.

The codices identified in the course of this research constitute a small group of manuscripts, mostly Gospels, which are being explored both from an iconographic point of view and as witnesses to other spheres of Armenian material culture, such as textiles. These portraits constitute a new starting point for broader research, which places them in comparison with Byzantine and Arab illuminated production with the same subject matter.

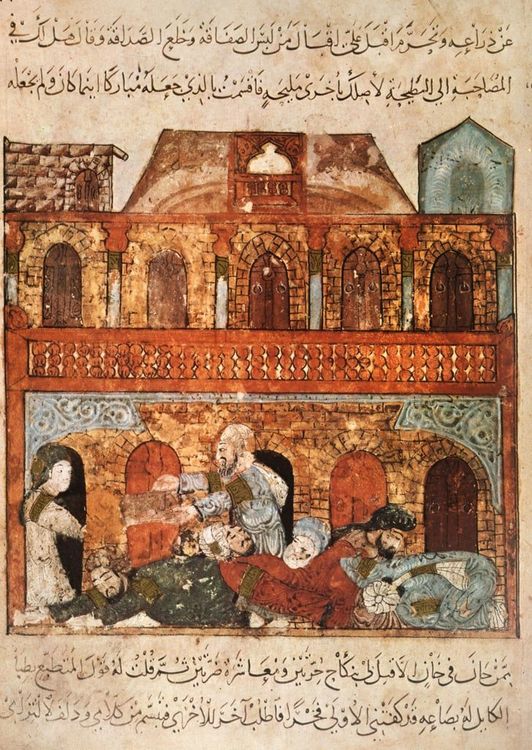

In the latter case especially, there are many images depicting trade and market scenes, such as a warehouse of merchants in the al-Maqāmāt manuscript, illustrated by the artist al-Wāsītī, dating to the 13th century and kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris (Fig. 2).

In the latter case especially, there are many images depicting trade and market scenes, such as a warehouse of merchants in the al-Maqāmāt manuscript, illustrated by the artist al-Wāsītī, dating to the 13th century and kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris (Fig. 2).

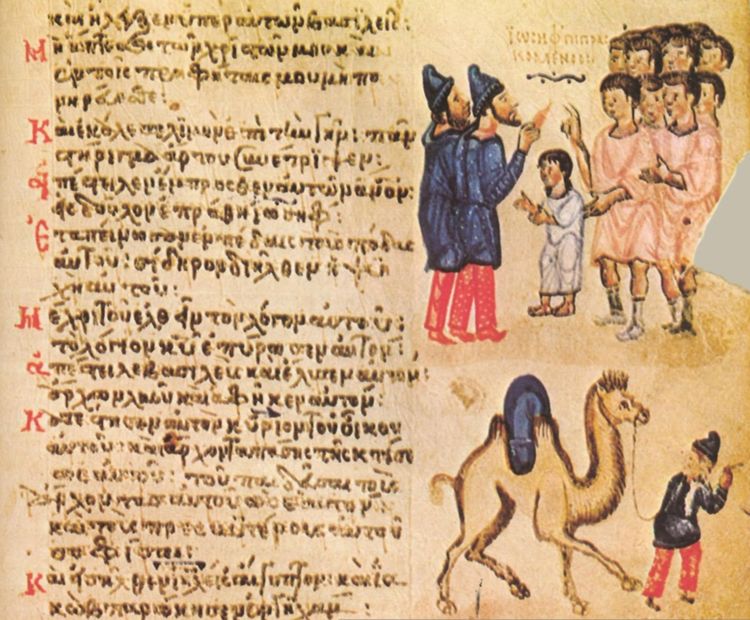

From the Byzantine repertoire, one may cite the (older) celebrated example from the famous Chludov Psalter. A series of marginal miniatures portray ‘Ishmaelite’ merchants who were the protagonists of a biblical passage from the Old Testament concerning the life of Joseph (Fig. 3).

How do these images compare to Armenian examples? The question will continue to guide my research as I uncover more Armenian examples.

Image sources:

Fig. 1: New Julfa (Isfahan, Iran), Monastery of the Savior of All, Gospel of Xckonkʻ, no. 36 (156), fol. 124v, year 1236. Sirarpie Der Nersessian, Armenian Miniatures from Isfahan, Brussels, 1986, fig. 45, p. 71;

Fig. 2: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Al Maqamat by al-Hariri, ms. Ar 5847, Meal in a caravanserai in Wasit: Abou Zayd has put his guests to sleep and takes their goods, fol. 89, c. 1240 AD, artist Yahya ibn Mahmud Al-Wasiti. Photo credit: Bridgeman Images;

Fig. 3 Moscow, State Historical Museum of Russia, , Ms. D. 129, Psalm 104, illustration: the Story of Joseph and the Ishmaelite Merchants, fol. 106, 9th century. Copyright Photos: Ziereis Facsimiles.

Last update

09.10.2022