New Discoveries: An Interreligious Disputation in Armenian and its Original

Intercultural and interreligious relations in the Middle Ages are reflected in numerous Armenian sources: historiography, theological treatises, canonical collections, biblical commentaries, letters, hagiography, fables, etc. Interreligious dialogues, however, are much less common in Armenian than intra-Christian (especially miaphysite vs dyophysite) debates. This is precisely why a newly discovered interreligious debate caused great excitement among ArmEn Project researchers. Its suggestive title is The Story of the Holy Monk Makar, the Emir, Aghtap‘ar, a Jew, a Nestor[ian], and a Sorcerer Who Believed in Christ.

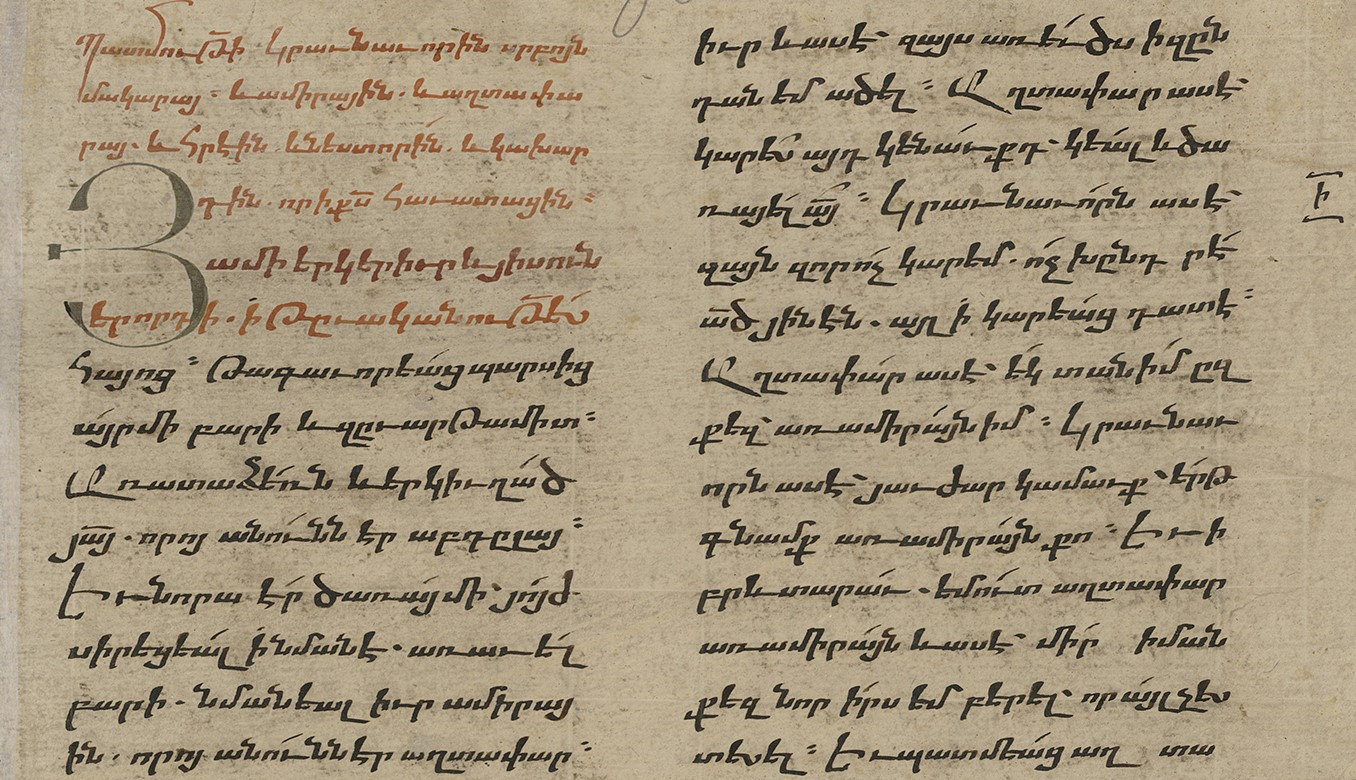

The exciting discovery was made by ArmEn’s team member Dr. Armine Melkonyan, as she was studying the content of a Homiliary manuscript in the Mashtots‘ Institute of Ancient Manuscripts -- the Matenadaran (Yerevan). The manuscript in question was copied in 1404 in the monastery of Nkarinay (in historical Vaspurakan, south of Lake Van). Her identification of the interreligious debate was a rather satisfying result of one of ArmEn project’s principal research procedures: to systematically explore the manuscripts labelled Homiliaries (Ճառընտիր), as well as similar types of codices classified as Collections or Miscellania (Ժողովածու). We were expecting these manuscripts to yield new textual sources that have remained outside the purview of historians. Dr. Melkoyan’s discovery confirms that this expectation was justified.

The Importance of Colophons

Like most Armenian manuscripts, our Homiliary has an informative colophon. We learn that its scribe was Grigor and that the commissioners were the monks Step‘anos and T‘umay, and the bishop Yohannēs. The debate occupies 50 folios and is divided into six parts. According to the marginal notes, it was read during the “First week of Advent”. In the course of further research, ten more manuscripts (mainly Homiliaries and Collections) were identified, housed at the Matenadaran, the Mekhitarist Congregation Libraries in Vienna and Venice, and at the repository of St James monastery in Jerusalem. The earliest copy is from the 12th or 13th century and comes from the monastery of Derdzki (in the town of Sebastia, presently Sivas in Turkey), while the latest is dated to 1746 (the place of copy is unknown).

The most interesting colophon is found in a manuscript dated 1441 (copied in Tayshogh, a village in Vaspurakan), as it gives us clues about the original language of this Story. It states that an Armenian king of the Andzevats‘ik‘ province (south-west of Vaspurakan, below Lake Van) “named Bardoghimēos, also called Apu Sahl”, translated this work from Arabic, when he was captured by the “infidels” (Muslims). Who is Bardoghimēos-Apu Sahl? We learn about him only through this manuscript and part of our future research will be aimed at identifying him and verifying his historicity. What we can hypothesize at this stage is that the translation may have been carried out during the captivity of some Armenian noblemen in the Abbasid capital of Samarra in the mid- to late 9th century. In any event, the presence of Arabic words and expressions in the Armenian translation, as well as references to some historical events in the text point to a Christian Arabic environment of the original text’s composition. Whatever the final outcome of our ongoing research, this text will enrich our understanding of Christian Arabic-Armenian translations, particularly those carried out in the 9th and 10th centuries, as attested by other texts.

The content of the Story

The supposed historical setting of the text has numerous anachronisms and unclear references. The Story claims to recount a debate that took place in the ancient Iranian capital of Ctesiphon in 801 AD, during the reign of “the Persian emir Abdlay” (in some examples Abdlaziz), who is presented as a generous and God-fearing ruler. The emir's beloved and faithful servant named Aghtap‘ar meets a monk called Makar while hunting and takes him to the emir. Almost the entire text is set up as a debate between the monk Makar on the one hand, and the emir Abdlay, an anonymous Jew, a Nestorian (who is simply called Nestor), and a “sorcerer” on the other. Their questions and answers deal with Christology, the nature of God and differences in the understanding of God between Jews and different groups of Christians and Muslims. It also addresses differences in religious and every-day customs. Some intriguing questions revolve around wealth and poverty, courage and cowardice, sexual practices, and the duties of servants and masters. We read very sharp and mutual accusations between Makar and his Jewish interlocutor. Makar blames the Jew for departing from the Law and for not accepting Christ, while the Jew criticizes Makar for Christian rituals such as the veneration of the Cross. Makar’s debate with the Nestorian, on the other hand, is mainly based on the writings of the Church Fathers, such as Gregory of Nyssa, Basil of Caesaria, Gregory of Nazianzus, Origen, and Clement of Alexandria. In the last part of the text, the emir invites a “skillful sorcerer” in order to have him convert the monk Makar to Islam. Yet, as is typical for such texts, the opposite happens: the sorcerer, as well as the emir and his servant Aghtap‘ar, convert to Christianity. They are soon baptized by Makar, acquiring highly significant new names. The emir receives the name Astvatsatur (Աստուածատուր, God-given), Aghtap‘ar becomes Christosatur (Քրիստոսատուր, Christ-given), and the sorcerer is named Khachatur (Խաչատուր, Cross-given). They isolate themselves in a remote desert in “the land of Cilicia” (according to another example “in the land of the Greeks”). Before retiring to the desert, the monk advises the emir to release all the prisoners and, particularly, to redeem those in Basra, one of the few geographical locations mentioned in the text that can give us clues as to the context of its composition. The Story ends with the death of the monk Makar.

The Significance of the Text

It is obvious that the author(s) of this debate aims to defend Christianity against Islam and Judaism. It is also clear that the main figure of the text, Makar, is representative of a strong anti-dyophysite and anti-Nestorian current. At the same time, he is well-acquainted with Islam and the Quran, which he cites, as well as with the writings of the Church Fathers, and some tenets of Judaism. The satire in the text is particularly remarkable. It makes the discussion of theological and religious issues engaging and entertaining.

Directions of Future Research

The discovery of this multi-layered text opens up several lines of investigation. First and foremost, a critical edition will be produced on the basis of the ten identified manuscripts. The Story enhances our knowledge on Christian Arabic-Armenian connections and translations. Although there is a relative dearth of interreligious debates surviving in Armenian, this discovery may indicate that there are more extant specimens. They simply have not been identified yet or attracted scholarly attention. The joint work of Zaroui Pogossian, Armine Melkonyan, and Barbara Roggema will aim at providing a full historical and source-critical commentary of the text, highlighting its significance as a historical source, its relationship with similar texts, for example in Arabic or Syriac, and as a witness to cultural interactions in the region of CAM.

Last update

23.11.2022